On the Body and the Space It Inhabits: An Interview with Elham Dawsari

Elham Dawsari is a is a self-taught sculptor, interdisciplinary conceptual artist, and writer based in Riyadh. She was born and raised in the Midwest and East Coast of the United States, and she later moved with her family back to Riyadh when she was 11. Dawsari has completed a month-long residency in Torrelles de Foix, Barcelona, Spain at the Mas els Igols Residency (February, 2020). She also majored in Accounting & Business Management at King Saud University and worked in financial advisory while also maintaining a freelance career as an illustrator. Through her illustration projects, she seized the opportunity to further specialize in creative content.

In this interview, she talked to us about the collective history of Saudi women in Riyadh, and her interest in studying how the experience of the body is shaped by the space it inhabits. She also highlighted her use of imagination and memory in filling archival silences and gaps in her work.

One of Elham’s first digital illustrations

Your work addresses personal and collective histories. How did your personal history shape your art interests and the topics you tackle in your work?

Personal and collective histories are crucial since I, like other Saudis from my generation and the one before it, used to be advised by my parents, aunts, and grandparents to document and record everything around us because a lot goes missing from our histories. They ensured that we record even if what we worked on didn’t end up in a report or research project — they told us it would gain importance over time. So documentation was something that had always existed in the back of my head as a kid even if I didn’t practice or pursue it.

Most of my work is a reflection of my childhood and memories. The personal anecdotes I focus on mostly stem from the turning point in my life in which my family moved from the US back to Riyadh when I was 11. I was very excited to go back to my home country that I had always heard of. The environment [in Riyadh] was different in various aspects, such as the street life, especially as they shape Saudi women’s experiences. That’s why I’m always thinking about the relationship between body and space, and how each one of them shapes our behaviors, especially Saudi women’s.

Historically, women have been connected to the land, whereas men were constantly moving and traveling for various purposes. This idea shaped and perpetuated women’s immobility and deepened their connection to the land, without consideration to whether this connection was created by force or not. Personally, I was very active as a child. I used to run and play football when my family lived in the US, but these hobbies were constricted when we moved to Riyadh, simply for being a girl. I shed light on such memories in my work — I drew myself in my first digital illustration as a kid sitting on our house doorsteps, watching other boys playing football barefoot. At that moment, we inhabited the same space. However, that space enforced constrictions on me that the other boys survived.

A girl, clown, and hypothetical bench

You focus in your work on variables that shape the human experience, such as space. What are some other examples of these variables, and what do they mean to you personally?

Space is crucial because it contributes to us, while we simultaneously contribute to it. There’s simply no functionality without space. What’s also important is studying the parts of spaces we inhabit that we can’t utilize, or where we can’t be fully ourselves depending on various factors, such as gender. I mostly felt constricted growing up. I also felt that my passions and interests were constricted and shaped by the spaces I inhabited.

I focus on variables like identity in my work. During my late teens and early twenties, I was constantly questioning and wondering what comprised our Saudi identity, and how we were different or similar to other identities in the Gulf. I also focus on landscape, and how it correlates to different geographies, especially in Riyadh.

I have lately come in terms with my identity as a Saudi woman living in Riyadh. And I’m always thinking about Riyadh, its landscape, and its women. For example, when I started driving, my point of view of the city shifted completely — I started viewing and enjoying Riyadh’s streets differently. I wasn’t aware that changing my position in that space would alter how I view it drastically.

Nfah

Saudi women are the center of your work. When you tell their stories to diverse audiences with different conceptions of them, how do you ensure you don’t portray them as a monolith?

There were many moments where I felt so pressured. I didn’t want to say, “I’m the only female artist, and my stories tell the story of every Saudi woman out there.” I specifically felt this pressure while working on Nfah. I initially described the project as a portrayal of Saudi women’s lives in Riyadh in the ’80s and ’90s. But I also ensured to explicitly mention that this portrayal was inspired by my personal experience and memory.

A lot of people related to this portrayal when they first saw the project. But I noticed women’s reactions differed when they came from backgrounds other than my own. After I exhibited the work for the first time in Jeddah, I noticed the different reactions of women, whether they were from Jeddah or visiting from other places. Even the women of Riyadh had different reaction because they lived in different areas within Riyadh — one of them told me I was generalizing, and another told me she didn’t experience such constrictions, even though she was from Riaydh.

These different reaction pushed me to ensure that I explicitly mention what each of my projects attempts to portray. For example, in Subabas, I mentioned that I’m simply sharing some of their stories, and not all, from a neutral, by-stander view.

Subabas: Tales of Sisterhood in Hospitality

Your writing and work revolve around marginalized identities. How do you ensure you consider the power dynamic that exists between you?

The Saudi art scene is still in its first stages, and we still lack a lot when it comes to training about handling this subject. For example, you could find luxury brands and magazine covers rudely taken in impoverished areas in Jeddah’s Al-Balad. I am glad a lot of people are paying attention and criticizing this new phenomenon.

Personally, when I started working on Subabas, I took into consideration that women’s voices generally go dismissed and erased. The voices of Subabas’ voices also remain even more forgotten due to their economic and social conditions. I clearly mentioned to each one of them every detail regarding the project. I also highlighted their rights throughout the process. Moreover, when I’m asked to be interviewed about the project, I ensure they’re present with me as it’s their story I’m telling — I’m simply the storyteller.

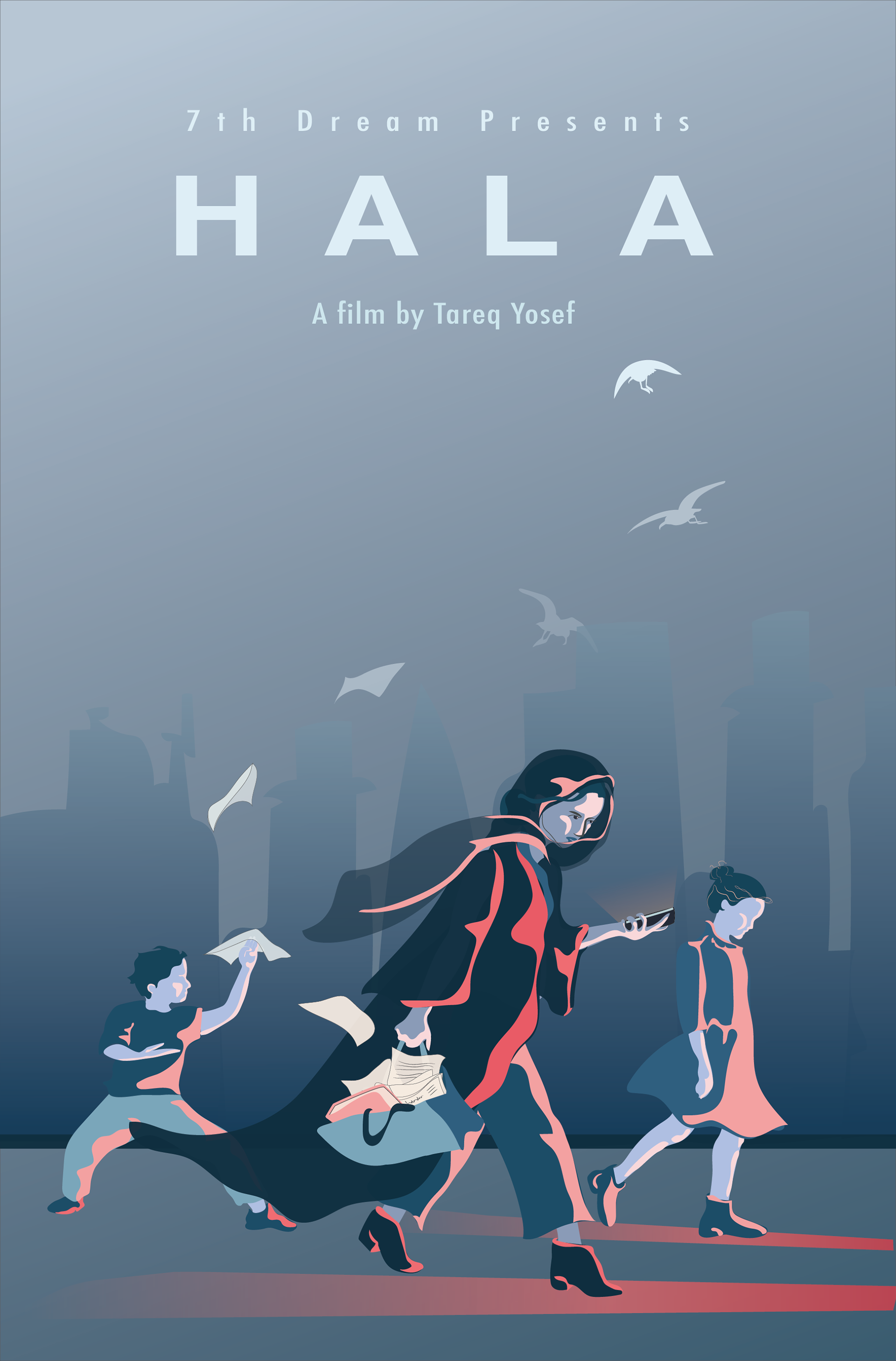

Poster design for Saudi short film Hala

Filling archival gaps and silences is also part of your work. What type of archives do you work with, and what is it about archives that intrigues you?

I didn’t think about archives at the beginning of my career. My work was an investigation of the past: how can I find certain information? Why are some difficult to find, while others are completely hidden? These questions led me to the archive, alongside my dad’s cameras and photo albums I grew up surrounded by. That’s why I was specifically interested in visual archives, and I was privileged to be part of a family that valued this type of documentation in an era where visual documentation was frowned upon in Saudi.

I found that women’s stories are forgotten and erased from visual archives. So I wanted to carry on my investigation in this regard. I was fortunate to be surrounded by artists and researchers who guided me while navigating different archives. When I started Subabas, I was hesitant about taking photographs of them to avoid taking advantage of their marginalization in any way. But director and writer Bayan Dawihis, who’s also one of my close friends, recommended that. Despite my hesitancy, I realized that I had a responsibility to fill such gaps, especially when it cam to the Subabas’ story I observed. My intention and purpose for photographing was solidified after I consulted curator Tara AlDughaither about using those photographs as a visual aid in my research. So I decided to push people to wonder and question why such stories go missing in our histories.

What is the importance of imagination and memory in filling archival silences and gaps?

Imagination and memory played a major role in Nfah. My project mainly relied on my family’s memories, photo albums, discussions, and other interviews. The physical records of that era to help me shape and portray different scene except for the photo albums my family had – they were scarce and rare. So imagination was the one of the main helped in depicting different aspect, such as women’s clothes and their bodies, to fill archival gaps.

Imagination was difficult to maneuver in other projects, though. I had to isolate myself and experiences and imagination from influencing my reporting and documentation of the Subabas’ stories. I only wanted to use their voices and stories and pictures to fill that gap.

Part of a motion graphic for the Saudi Commission of Tourism and Heritage